C.A.T.S. presents new, morbid art show in the A*Space

Perhaps the most successful part of The Death Show, on view the evening of February 28th in the A*Space, was that it avoided all stereotypical and clichéd images of death. Death scares us for a number of reasons, chiefly because of its unknowable qualities. How can we cope aesthetically with the unknowable, with the end of aesthetics? The fact that curators Dashael Nadler and Jonathan Worcester chose such a pithy, straightforward title for their show adds a touch of frivolity to such a fearsome theme, a theme that few exhibitions (if any) have attempted to tackle head-on. The title points references to, among other things, death metal, Freud’s idea of the death drive, and Roland Barthes’ “Death of the Author.” This choice calls upon theories of the posthuman, which recognize imperfectability and disunity within the self, the creation of meaning through play, and situated (rather than universal) objectivity. The eight artists included in the group show all address death in idiosyncratic, abstracted ways, examining mortality in terms of absence and presence, lightness and darkness, the body and the spectacle.

Upon entering the space, Eben Woodward’s installation piece was the first to jump out, perhaps due to its palpable weight in the space. In a video projection, he is wrestling with a hefty, deformed concrete and metal sheet. He struggles with it, halfway out of the camera frame, straining under the physical weight of the piece—the strength of his body is tested against the strength of the concrete as they battle each other. The detritus of the construction lies crumpled in front of the video projection, as if the artist won the battle and now displays the carcass as a trophy in its mausoleum, the gallery. In college, sculptors frequently face a choice: they either must find somewhere to store their larger works or they must destroy them. The act of destroying old pieces can become cathartic as the artist demolishes relics of the past in order to move on with future projects, knowing that he can recreate these works in the future if he needs to.

Just to the right of Woodward’s installation hang two small, abstract works on circular paper by Worcester. Volatile waves of color swell beyond the minute, delicate pieces of paper, which come to appear even less solid when caught up in the vibrant flow of materials. Paintings are necessarily subjected to time, steadily decaying. Worcester’s paintings respond to this limiting bodily lifespan by exuding an uncontainable radiance. His video piece, tucked away in the back of the space, also examines naturally occurring abstractions and abandoned places, shifting between a tone of dreamy optimism that believes in transcendence and a cold reality principle that knows that our dreams are always bounded by materiality.

Nadler’s piece for the show, a three-dimensional, star-shaped structure of bare wood, encases and suspends a syrupy mess of hair and plaster. It alludes to the suspension of soft, ephemeral substances in hard, enduring materials. Finality is eternally delayed, prolonged by the tough, physicalized tension of internal and external.

Two seemingly divergent but actually closely related perspectives on death frame the entryway to A*Space: Lily Rosner’s all white painting, recalling modernist abstraction and minimalism, and Jack Califano’s photo series of mangled wild animals. Califano’s gruesomely explicit close-ups of dead animals transform the lifeless bodies into mere spectacles, this compelling a detached, clinical inspection and an aesthetic fascination with the surface. Rosner’s piece refuses ease of access and shows no image at first glance. But after inspection, the canvas reveals a subtle design hidden just beneath the surface. These differing pieces converge in a dialogue concerning the nature of the image and the information it can offer us.

Just to the left of these hang an expressionistic portrait by Rahul Dhakal and a small, bright abstract painting by Emma Niwa. The intense expression of the man in Dhakal’s portrait paired with the thick, hurried brushstrokes of paint convey anxiety. It is as if he was trying to capture the frenetic sensuousness of the figure in paint but could not because the moment passed too quickly. Niwa’s work is the quietest of the show, solitary but brimming with a melancholy brightness. Both fall in line with more traditional methods of painting, but their inclusion in the show offers them as memorabilia of loneliness, an intimacy we reach for but can never truly or permanently hold on to.

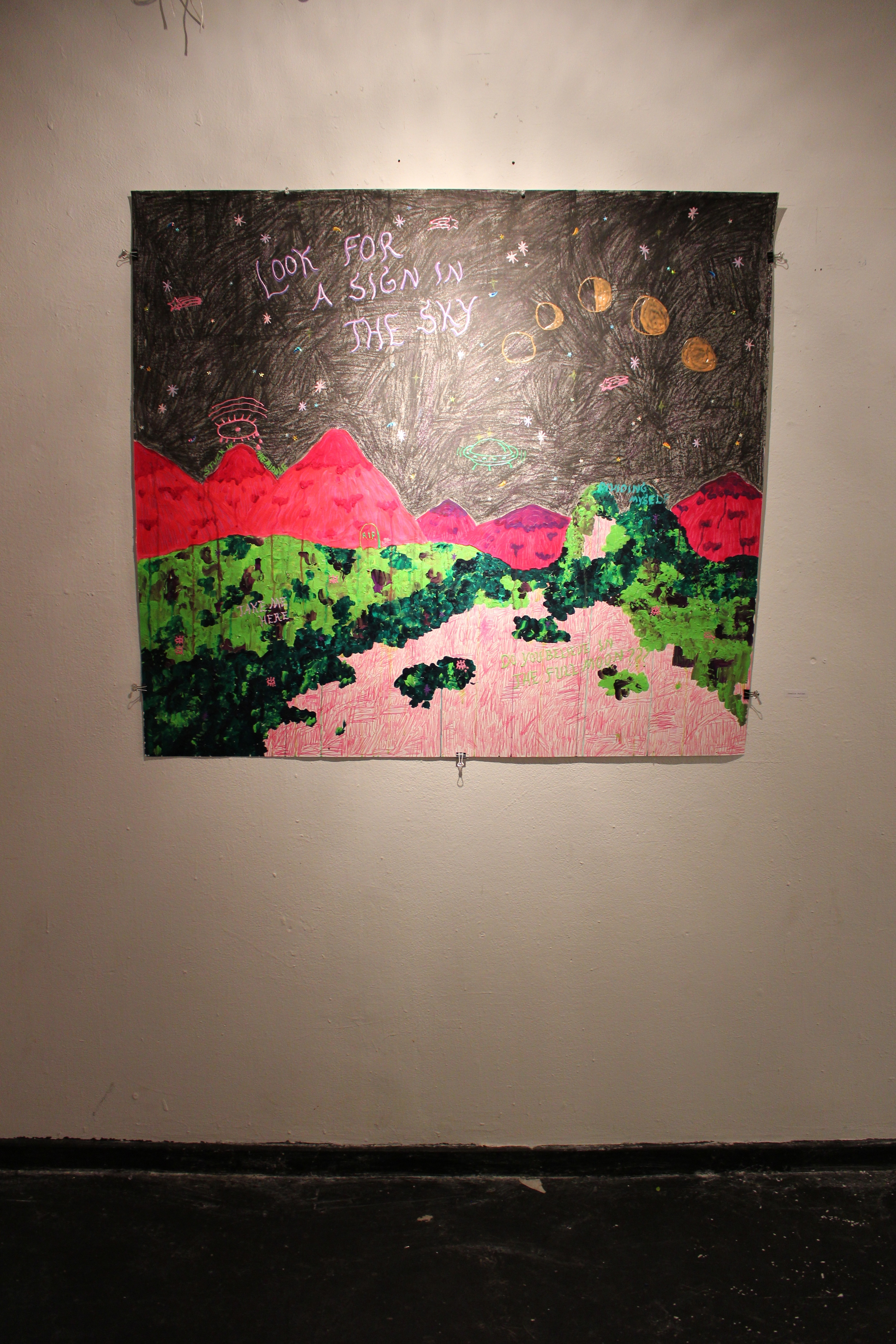

The show includes one other series of photographs, which shares a wall with Woodward’s piece and speaks to similar ideas of presence, absence, and the tension between the ephemeral human body and the landscapes, both actual and virtual, which persist beyond them. Contributed by an anonymous student, the photos depict people moving through public space, where either the bodies themselves or the landscapes that surround them are erased. Arranged in vertical pairs on the wall, the top row of photos depicts landscapes with the people eliminated, their spaces filled in glowing white silhouettes. In the bottom row the landscapes are erased and the people are left floating in bright color-fields of glitched pixels. The series questions how our perception of environments is affected when a body is censored, when it’s absence is made present, or how a body is experienced when its’ context is displaced. It shows us how a body might feel when it is isolated in a virtual landscape.

The Death Show is one of the most cohesive shows organized with the backing of Creative Arts Thinking Space (C.A.T.S.: a non-hierarchical collective of artistically minded individuals who work together to present shows, artist talks, workshops, and other events around campus). The curators resist offering a conclusive, didactic definition or representation of their theme, leaving space for various personal responses. They do so successfully by enacting the tension between permanence and ephemerality, material objects and immaterial energies in the show. The Death Show approaches this tension with a lighthearted tone, which can afford to be playful precisely because it contemplates death aesthetically from a distance. Death is something we all must deal with eventually, but in different ways. It is one of those universal experiences which remains simultaneously personal and impersonal. If the show does posit something definitively, it is perhaps that the responses to death can only be discovered as we face smaller deaths in life, when it seems our agency over processes has come to an end. Something, however, might persist, even when we think we have destroyed past relics to make room for future enterprises. We all have our ghosts.

by Colleen O'Connor '15

coconnor1@gm.slc.edu

fictivesisters.wordpress.com