The Lasting Legacy of the College Center for Continuing Education

Ainsley Wilkinson ‘23

Photo by Sarah Lawrence College Archives

Sarah Lawrence welcomed its first students in 1928, and the women who attended college in that time were defying convention. For nearly 40 years after the college’s founding, many female students had to leave the school to marry and raise families and had no way to return and finish their degrees. The Sarah Lawrence College Center for Continuing Education (CCE) was established in 1962 to address this problem. Esther Raushenbush came to Sarah Lawrence in 1935 as a literature professor, progressing to Dean of the college from 1946 to 1957, and then President of the college from 1965 to 1969. She proposed the CCE as a degree-pursuing program extending to any applicants in the Westchester area, not just former Sarah Lawrence students, and obtained a grant from the Carnegie Center to establish the Center in 1962. The impact of the CCE on returning students’ lives was immense. A Sarah Lawrence school newspaper issue published in 1989 conveyed their experiences and opinions.

“Although their reasons for withdrawing from school years ago vary ([Pat] Frederick was "swept off her feet" and married after sophomore year, while others departed for a taste of the outside world), all the students were compelled to return by the desire for completion. Similarly, each woman is deeply satisfied with her current studies and believes that she is now taking full advantage of her opportunity to learn. Cathy Drake, originally a freshman in '80, finds that she is "much more excited about the work now. It's a lot more relevant to my life."”

The heart of the CCE’s goal and structure was to work with returning students to formulate an education plan that worked best for them individually. A program brochure from one of the first years of the operation explained that the Center would work with students to help them find their own way in which they may pursue their studies. This planning involved studies at Sarah Lawrence College, studies at other institutions, or special plans appropriate to the individual situation.

The 1970-71 class saw a third of its population between the ages of 31-35, with groups 36-40 and 41-45 having just slightly fewer numbers. There were five students who were over the age of 51. Older adult learners bring life experience and educational needs that have a range far greater than undergraduates who sit mostly between the ages of 18 and 22. The CCE’s supportive arrangements were designed for older students specifically, offering counseling targeted at an older population while ensuring that class meeting times avoided when students’ children may be out of school. Existing helpful structures like donning were extended to these returning students. Courses were described as determined by the needs of individuals seeking to enter the program.

“The approach was absolutely pioneering,” says Susan Guma, who worked for the College for 30 years starting as Associate Director of the CCE and eventually becoming Dean of Graduate Studies. “They really enjoyed being able to work with the faculty in a variety of areas. It gave them the time and support, because we had the donning system for them, so that they were really able to explore where they wanted to be.”

Esther Raushenbush’s 1974 written report, “Some Reflections on Continuing Education,” highlights SLC’s compatibility with the rich and involved type of education that these older students needed – a core aspect of the CCE. She notes, “small classes, the emphasis on discussion of what one has read or done, on interchange, on thinking. Less on just listening and recording.” There was an underlying goal of the Center to not just help older adult learners finish their degrees, but to holistically open their minds to their own potential as well as the breadth of career options available.

As early on as 1971, a General Committee meeting reported weariness about the Center’s curriculum being “pinched” due to financial reasons. Greater integration of the Center with the College was recommended in the interests of curriculum coordination, though there were difficulties in finding faculty from the College to teach for the Center. The same General Committee report also cites the school’s inability to hire more part-time teachers and an overall increased administrative workload as issues that threatened the CCE’s future.

In the spring of 2011, the Office of Special Programs merged with the CCE. An April 2012 issue of The Phoenix headlines “The Center for Continuing Education Celebrates Fifty Years” and boasts Sarah Lawrence’s continuation of assisting returning students in pursuing their degrees. As of now, a search for the CCE on the SLC website finds no current office or programs.

The Center’s final years may have been more of a transformation than a dissolution, but that depends on who you ask. A pillar of the CCE was the multi-faceted support that returning students were granted throughout their acclimation back into academia. Reflecting on what the CCE offered to students then and now tells a fuller story of what may have been gained, or lost.

“We had a number of people that had a master’s, or had a bachelor’s,” Guma says, “and they were just looking at a small college that had a strong background in liberal arts where they could really explore areas that they wanted to go into.” Over decades, the number of older students who were returning to finish a B.A. diminished, and that programming was superseded by other graduate and professional services provided by the CCE.

“The needs of the students that we were seeing matched much more with professional education and graduate areas,” Guma added. “They were more looking at that next level of engagement.”

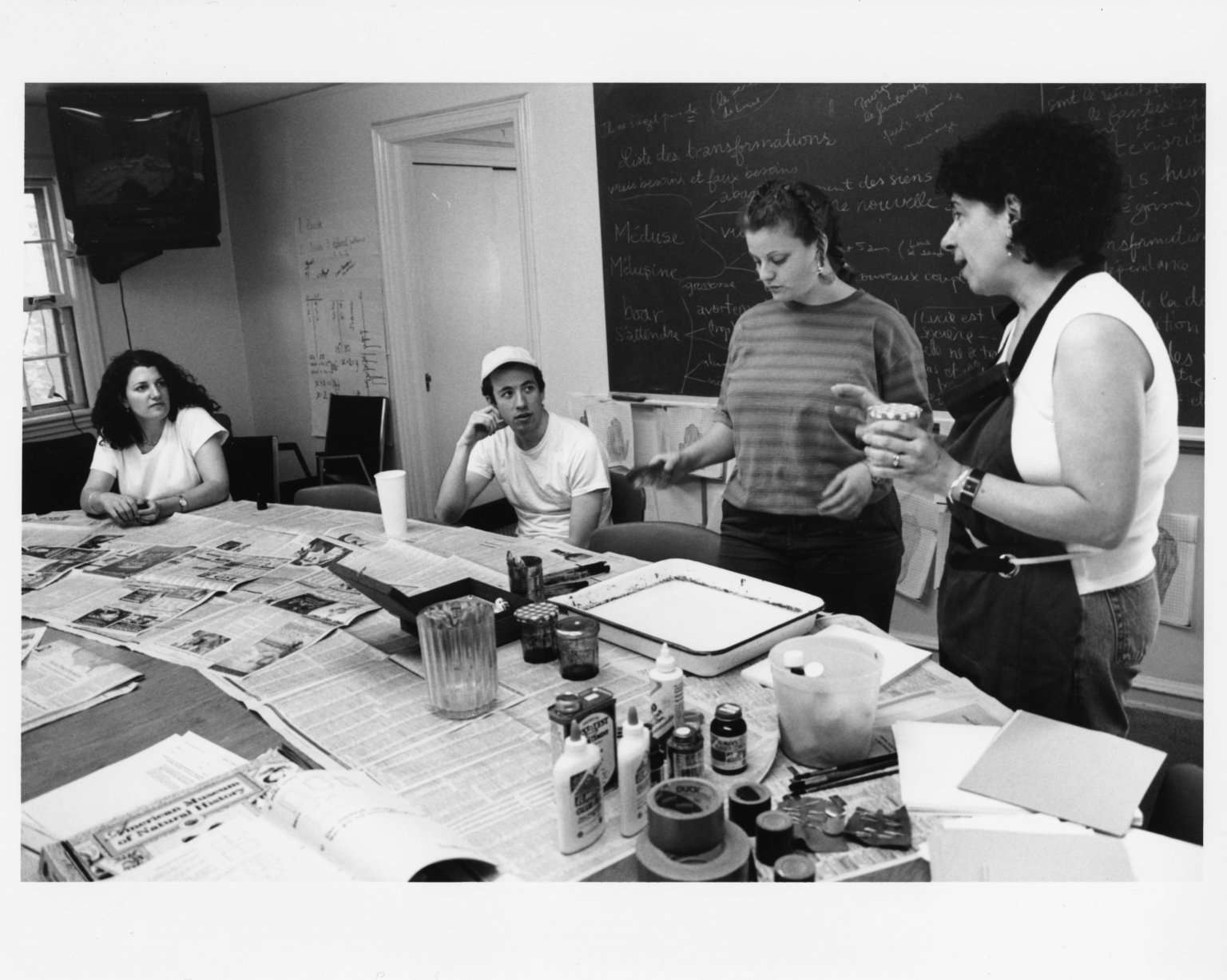

Art of Teaching graduate program classroom, 1980’s, via Sarah Lawrence Archives Facebook

In addition to a shift in the need for adult and continuing education, there was also a general dispersal of that need among other schools. Sarah Lawrence was one of the very first colleges to introduce a designated department for continued education, and this stemmed from its all-female student body and how common it was for women to leave their degrees prematurely at the time. As higher education developed over the following 50 years, alternative programs for adult and continued education sprung up nationwide.

Enrollment records show that up through at least the 1970’s, the CCE was only growing. The 1962-63 school year reported 33 students at the Center, which jumped to 65 students by the 1970-71 school year. That further grew to 88 students only two years later. There are no publicly available enrollment records for later years, but an informational booklet for the CCE from 2006 lists available courses for both the Center itself and other professional programs and institutes at Sarah Lawrence. The number of courses and workshops listed suggests that the programs were still well-attended in later years, although they may have pertained less to pursuing a B.A..

“Whether it’s a community college or an Ivy, they all have continuing education departments and they’re all big departments,” Guma says. “All of that emerged, so people did not have to seek us out to complete those degrees.”

Enrollment declined, and the enrollment that remained was heavily focused on professional programs and enhancing students’ already-developed careers. In response, SLC reduced its emphasis on finishing degrees and shifted their efforts towards career supplementation and graduate studies.

Now, the most priority has been placed on graduate studies. Sarah Lawrence hosts 10 successful master’s degree programs that total to over 300 graduate students. Contrastingly, under professional studies there is only information available for three separate programs: Health Advocacy, the Writing Institute, and the Child Development Institute. The Health Advocacy program provides opportunities for various certifications alongside virtual events and workshops. The other two institutes provide virtual days and weeks-long workshops, in-person lectures, and DVD programs.

Other once-successful professional programs like the filmmaker’s collective and filmmaker’s week have had their information reduced to a “404: Page Not Found.” It is the notion of what programs were once offered that is disappointing. A public booklet from 2014 still advertises the B.A. completion program and post-B.A. studies with the CCE, alongside numerous 11-week courses and other 5-week courses with the Writing Institute.

A large part of what left the school along with the CCE was the intermingling of older returning students with undergraduate students. The mixing of age groups was generally seen as an inspiring and advantageous classroom dynamic. Excerpts from the same previously-mentioned 1989 issue of the SLC newspaper corroborate.

“Connie Bailey, originally a freshman in '71, has also experienced respect for contemporary students. In her writing class, she observes, ‘I'm 37 and I sit next to someone who's 18 years old and writes like I wish I could write. I don't know where it comes from.’”

“‘Watching women grow, that's been fun,’ observes Frederick. ‘In the class watching the class come together, watching the teacher adapt to us as we've adapted to her, and sort of coming together like a family so that we understand what we're talking about— it's a wonderful feeling.’”

There are some graduate programs that remain open to integration with undergraduate courses, primarily theater, dance, and writing. For graduate students, this keeps the door open for a greater range of connections, though these are mainly connections with faculty. A large part of graduate studies stays confined to its hub in Slonim House, as well as Wrexham which hosts the health-related programs.

Students socializing outside, 1970s, via Sarah Lawrence Archives Facebook

It was special for SLC’s unique pedagogy to converge with a welcoming of older students back into a close-knit academic environment where they could finish their degrees while being able to explore new areas. It may not be a question of bringing back the CCE or other adult programs that have faded out of sight, but rather how we can invigorate the connection between younger and older student populations at this school to regain some of the advantages that early students of the CCE and their surrounding undergrads felt.

Guma notes, “Particularly in a school like Sarah Lawrence, there is the real luxury of teachers being able to provide rich resources and interaction between the two populations.”